Se Busca Terreno en Colombia

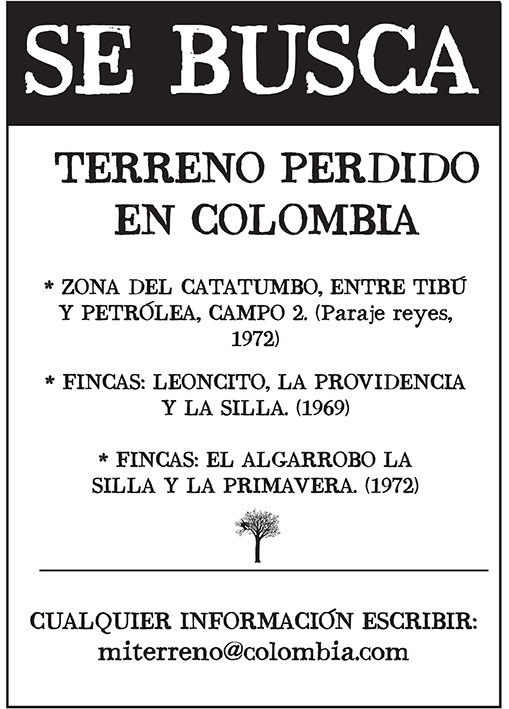

“Looking for a plot of land in Colombia” is the title of a poster pasted on the streets of Cúcuta. It refers to a piece of land in the Catatumbo region — a land that exists in documents — in deeds, in the land registry — but cannot be found, cannot be seen, cannot be inhabited.

This simple gesture — posting a flyer — unveils a deeper reality: in Colombia, many lands exist only on paper. Their legal presence contrasts with their physical, material, historical absence. These are lands made invisible, stripped of body and voice.

The Catatumbo, like so many regions scarred by violence, bears a history of open wounds. The land, instead of offering refuge, becomes a broken promise. Indigenous peoples such as the Barí have been displaced time and again by external interests: oil, profit, control. Their memory — like that land — endures, even when there are efforts to erase it.

This poster is not just looking for a plot of land. It points to an absence — and within that absence, the urgent need to rethink our relationship to territory, rights, and belonging.

« On recherche un terrain en Colombie » est le titre d’une affiche collée dans les rues de Cúcuta. On y mentionne un terrain situé dans le Catatumbo, inscrit dans les documents — l’acte notarié, le cadastre — mais qui ne se laisse pas voir, qui n’apparaît pas, qui ne peut être habité.

Ce geste simple — coller une affiche — dévoile une réalité profonde : en Colombie, de nombreux territoires n’existent que sur le papier. Leur présence légale contraste avec une absence physique, matérielle, historique. Ce sont des terres absentes, invisibilisées, dépouillées de corps et de voix.

Le Catatumbo, comme tant d’autres régions marquées par la violence, porte une histoire de blessures ouvertes. La terre, au lieu d’abriter, devient promesse rompue. Les peuples autochtones, comme les Barí, ont été déplacés encore et encore par des intérêts extérieurs : pétrole, profit, contrôle. Leur mémoire — comme ce terrain — subsiste, même si l’on tente souvent de l’effacer.

Cette affiche ne cherche pas seulement un terrain. Elle désigne une absence. Et dans cette absence, l’urgence de repenser le lien entre territoire, droit et appartenance.

This simple gesture — posting a flyer — unveils a deeper reality: in Colombia, many lands exist only on paper. Their legal presence contrasts with their physical, material, historical absence. These are lands made invisible, stripped of body and voice.

The Catatumbo, like so many regions scarred by violence, bears a history of open wounds. The land, instead of offering refuge, becomes a broken promise. Indigenous peoples such as the Barí have been displaced time and again by external interests: oil, profit, control. Their memory — like that land — endures, even when there are efforts to erase it.

This poster is not just looking for a plot of land. It points to an absence — and within that absence, the urgent need to rethink our relationship to territory, rights, and belonging.

« On recherche un terrain en Colombie » est le titre d’une affiche collée dans les rues de Cúcuta. On y mentionne un terrain situé dans le Catatumbo, inscrit dans les documents — l’acte notarié, le cadastre — mais qui ne se laisse pas voir, qui n’apparaît pas, qui ne peut être habité.

Ce geste simple — coller une affiche — dévoile une réalité profonde : en Colombie, de nombreux territoires n’existent que sur le papier. Leur présence légale contraste avec une absence physique, matérielle, historique. Ce sont des terres absentes, invisibilisées, dépouillées de corps et de voix.

Le Catatumbo, comme tant d’autres régions marquées par la violence, porte une histoire de blessures ouvertes. La terre, au lieu d’abriter, devient promesse rompue. Les peuples autochtones, comme les Barí, ont été déplacés encore et encore par des intérêts extérieurs : pétrole, profit, contrôle. Leur mémoire — comme ce terrain — subsiste, même si l’on tente souvent de l’effacer.

Cette affiche ne cherche pas seulement un terrain. Elle désigne une absence. Et dans cette absence, l’urgence de repenser le lien entre territoire, droit et appartenance.

"Se busca un terreno en Colombia" es el título de un afiche pegado en las calles de Cúcuta. En él se nombra un terreno en el Catatumbo que existe en los documentos —en la escritura, en el catastro—, pero que no se deja ver, que no aparece, que no puede ser habitado.

Este gesto sencillo —pegar un afiche— revela una realidad profunda: en Colombia, muchos territorios habitan solo el papel. Su existencia legal contrasta con una negación física, material, histórica. Son tierras ausentes, invisibilizadas, despojadas de cuerpo y de voz.

El Catatumbo, como tantas regiones marcadas por la violencia, arrastra una historia de heridas abiertas. La tierra, en lugar de cobijar, se convierte en promesa rota. Los pueblos indígenas, como los Barí, han sido desplazados una y otra vez por intereses ajenos: petróleo, ganancia, control. Su memoria —como ese terreno— permanece, aunque a menudo se intente borrar.

Este afiche no solo busca un terreno. Señala una ausencia. Y en ella, la urgencia de repensar la relación entre territorio, derecho y pertenencia.

![]()

Este gesto sencillo —pegar un afiche— revela una realidad profunda: en Colombia, muchos territorios habitan solo el papel. Su existencia legal contrasta con una negación física, material, histórica. Son tierras ausentes, invisibilizadas, despojadas de cuerpo y de voz.

El Catatumbo, como tantas regiones marcadas por la violencia, arrastra una historia de heridas abiertas. La tierra, en lugar de cobijar, se convierte en promesa rota. Los pueblos indígenas, como los Barí, han sido desplazados una y otra vez por intereses ajenos: petróleo, ganancia, control. Su memoria —como ese terreno— permanece, aunque a menudo se intente borrar.

Este afiche no solo busca un terreno. Señala una ausencia. Y en ella, la urgencia de repensar la relación entre territorio, derecho y pertenencia.